* Anthropoid Coffins from Deir el-Balah *

How were these Coffins manufactured?

by Dr. Jan Gunneweg

Archaeometry Unit,

Institute of Archaeology

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem,

Israel

Introduction

Since the anthropoid burial coffins, found in Deir el-Balah and

situated in the dunes 14 kilometers south of Gaza, first emerged

from anonymity, (T. Dothan 1979) the question of how these almost

two meter long ceramic coffins were manufactured, has become

intriguing.

*

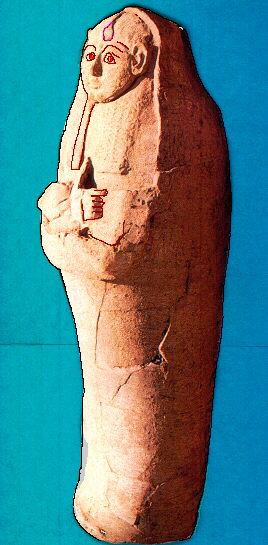

Anthropoid Coffin

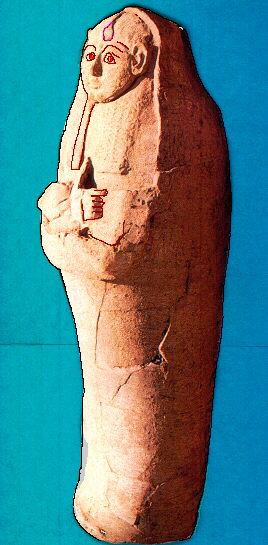

The anthropoid coffins are large ceramic recipients made to

hold a corpse for burial. They are cylindrical and conical in

shape. Two-thirds up from the bottom, the cylinder is of one

piece, whereas at a third or a quarter length from the top, a

slab was cut out from the main upper structure to enable the

insertion of the deceased. The same removed slab of clay would

later serve as a detachable lid which would cover the open space

of the coffin after the corpse had been inserted. The average

length of a coffin is between 1.94 to 2 meters, and a few coffins

are less (one even 1.60 m., which is exceptional) (Dothan 1979,

99). Its width is about 0.60-0.75 m. at its shoulder and 0.40-

0.50 m at its base. The coffins at Deir el-Balah are dated to the

Late Bronze II and Iron Age I. Their origin, as a concept, lies

in Egypt (W. F. Albright, 1932, 295 ff; Petrie 1888; Neville and

Griffith 1890; Reisner 1910 and Engelbach 1915), where similar

coffins have been unearthed, but these were made of a variety of

materials: wood, plaster, ceramic and stone, and the ceramic ones

were inferior in quality to the those found in Deir el-Balah.

Others of the same period were found in Canaan (Petrie and

Tufnell 1930; Rowe 1930 and Macdonald et al. 1930) and in Syria

(Hennequin 1939).

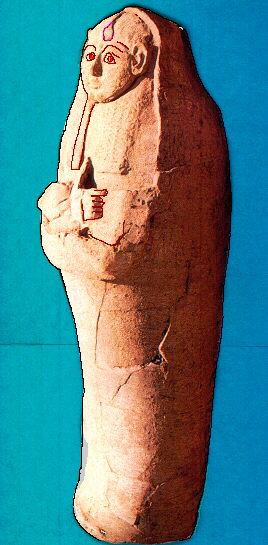

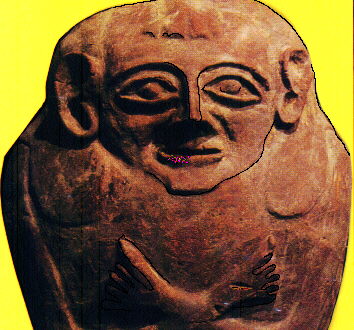

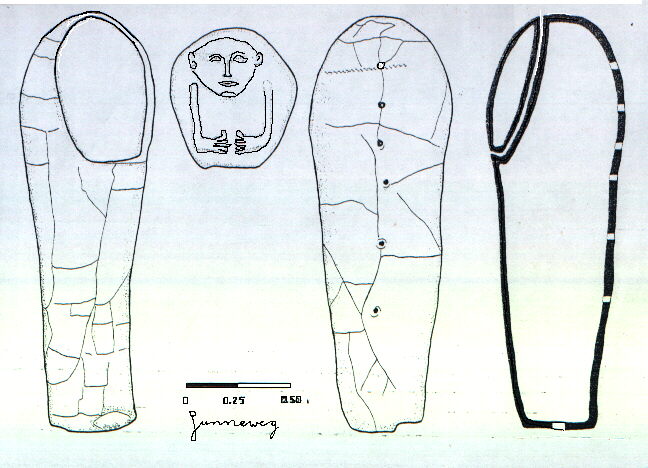

The removable lid measures about 0.65 by 0.50 m., adorned by a

modeled face, made by means of clay appliques and incisions. The

lid depicts a mouth, eyes, a nose, ears and often a wig, features

sometimes accentuated by white, black, red and gold colours. Many

of the lids bear stylized arms and hands. Most of them have been

unearthed in legal excavations (Footnote 1), whereas the minority

was dug up illegally (see the M. Dayan collection).

Coffin Lid

The purpose of this study

The purpose of this study is to examine the technique used to

manufacture such a coffin. To date, all the scholars who have

dealt with this problem have asked themselves how were these

coffins fired. Some scholars have come up with a plausible

answer. T. Ornan summarized it in 1986 as follows: "The coffins

and lids were probably fired in an open fire at a relatively low

temperature, and the lids were then fired a second time at a

higher temperature in a kiln" (Ornan 1986, 120). She continues:

"Potter's kilns containing coffin-fragments which were excavated

in the settlement [of Deir el-Balah, insertion mine] near the

cemetery, demonstrate that the coffins were produced at the site"

(idem, 121). Perlman had determined the local manufacture of the

coffins long before 1986, on the ground of neutron activation

results (Perlman et al. 1973, 149). No different ways of firing

the coffins are known to me from the published material.

Because of the sheer absence of a large kiln needed for firing

such a coffin and the near impossibility of an 'open-firing' of

it, I propose the following: The basic premise is that the

coffins were fired neither in the open, nor in a kiln, at least

not in one as we know it today from the usual kiln firing. In

some peculiar way, the coffin itself must have served as the

kiln, as I will explain.

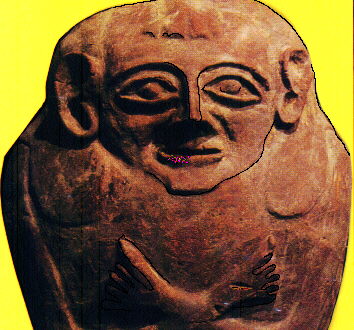

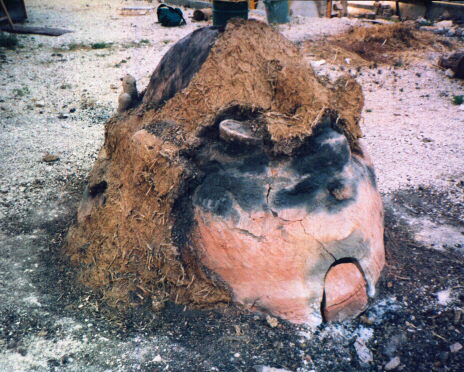

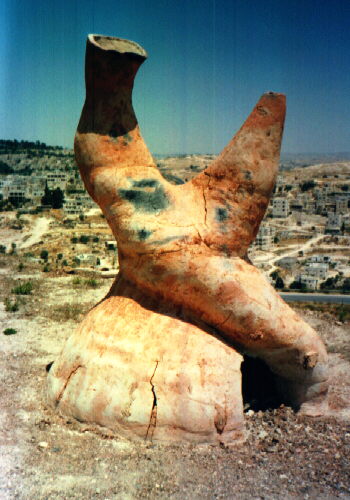

In the Spring of 1994, a team of students at the Jerusalem Art

School of Bezalel experimented with a project for making art-

pottery, which consisted of firing huge statues made of clay. The

leader of the class, Martina Schoder from Altenstadt in W-Germany

taught her students how to fire larger than life-size ceramic

objects. Her class created a statue which is shown in Fig. 1a.

in Fig. 1a.

Bezalel's Ceramic Structure

Back at my desk at the nearly adjacent Institute of Archaeology

in the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, it suddenly occurred to me

that here one may perhaps find an explanation of how Late Bronze

anthropoid coffins were made in Deir el-Balah and elsewhere.

The coffin

The ancient potter would have proceeded as follows: First, the

coffin was freely hand-made by means of the coil technique. The

body of the coffin was formed, while smoothing over the inside

and the outside as work progressed.

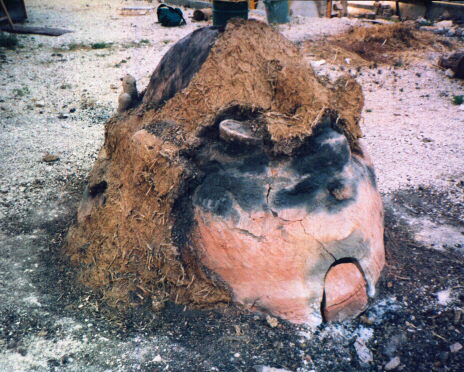

Bezalel's "kiln-Art-Piece" Structure

The coffin was made of one piece until the top was reached and

closed. Three to five holes, each 2 cms diameter,--whose function

is to be

explained later--were pierced through the back of the coffin and

often a hole was cut at the foot end, or some holes were pierced

through it. There are no such holes in the front of the coffin.

When the coffin was dry enough to support itself, a string was

taken and a symmetrical cut was made throughout the entire upper-

front

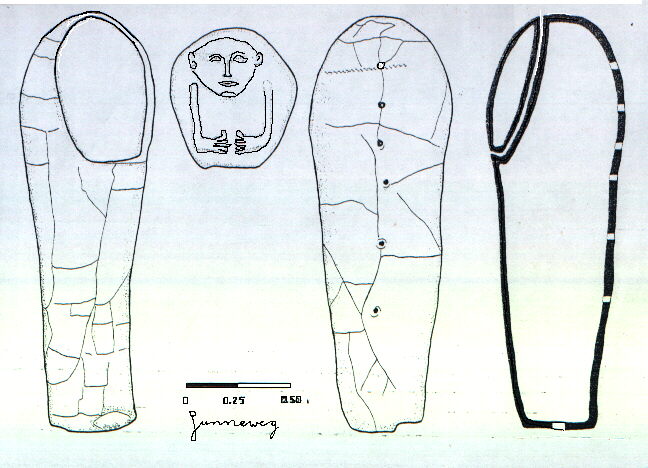

Anthropoid Coffin in section

This explains why the sides of the cut on both the lid and the

coffin are smooth, without the potter having to be afraid that he

would come out at a different place,

in case he used a knife. The slab (the lid) was not removed

until the whole construction was thoroughly dried. Only then,

were both separated.

The lid

The lid was modeled in high and/or low relief as described in

the Introduction. It was then dried and fired in a kiln. Kilns

with fragments have been found near the cemetery (Ornan 1986,

121). Therefore, there was no incentive to fire the lid twice as

Ornan has suggested. Her statement is based on the rope

impression found on one of the coffins which, according to her,

indicated that both, the coffin and the lid, were first fired

together in an open fire (see our drawing of the anthropoid

coffin which is a free pen-

tracing of Ornan's photograph 57:3). However, the rope could not

have made the impression found at the back of one of the coffins,

when it tied the two separable parts after the coffin had become

bone hard; the rope would not have left an impression. And if it

did leave one, its traces on the front of the lid as well had to

be found. These have not been found.

The signs of a rope impression probably mean that at the point

where the coffin was the weakest, a string was used to support it

until it would be dry. The rope left its impression on the back

of the coffin because it was put there when the coffin was wet,

before the cut-out lid was removed for the modelling of the face.

It served the purpose of keeping the shape of the coffin after

the lid had been cut out. Then, one worked on the lid, dried it,

and fired it separately--a hypothesis which can be proved because

of the finds of it in the kilns unearthed.

The kiln

The next step was to build the kiln. For that purpose, a narrow

shallow--50 cms. deep--V-shaped ditch was dug into the ground

which started at 50 cms from the head-end of the coffin, at the

part where the opening for the corpse was cut out. The ditch

continued beneath the entire length of the coffin, until 40 cms

beyond its rear end. From the head-end outward, a slope was dug,

which served as the entrance of the firing tunnel. Thereby, care

was taken that the stoking hole would be deep enough to allow the

ashes to fall down into the hollow without blocking the draft or

obstructing the re-fueling of the kiln.

The coffin was placed bottom-up over the V-shaped ditch to a

depth where the cut-out lid-space became level with the

surrounding ground. The coffin was to a depth of 15 cms into the

ditch, whereas the rest stuck out above ground. Since the V-

shaped ditch was 50 cms deep, one obtained some sort of a wind

tunnel below the entire length of the coffin.

Then, the front of the V-shaped ditch which was visible, was

covered with a roofed construction of clay, mud and straw,

forming a stoking chamber positioned at the head-end of the

coffin. Thus, the hot gases of the fire could easily enter the

inside of the coffin through the cut in the coffin, as well as

below the entire structure

Coffin used as its own kiln

(see Fig

3.).

At the other end of the V-shaped ditch, a construction of

either stones or bricks and mortar was built on which a chimney

was placed. The chimney of the kiln could have been made of

bottom-less store jars covered with wet mud mixed with straw cut

into pieces of 15 cms length. A shard of a vessel would have had

to be at hand to be placed on the chimney opening in order to

muffle the escaping fumes. The position of the chimney in terms

of whether it was situated opposite the wind direction or not, is

unimportant, because the hot smoke which escaped the kiln through

the chimney would have created a natural draft, irrespective of

the direction of the prevailing wind.

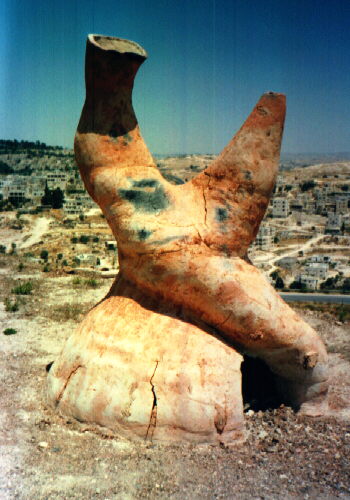

If, as was described above, this construction were to be fueled

by supplying the stoking ditch with branches, dung, wood, straw,

thistles and the like, and lit, the entire enterprise would

certainly have been a failure, because the coffin would either

have exploded or disintegrated. Heaping fuel around and over it

would momentarily give a fierce fire, but this would not suffice

to turn a 3 cm thick and almost two meters long structure of clay

into a ceramic. Heap firing suffices for small and medium large

vessels.

The proposed manner of firing

Therefore, something is needed to prevent the coffin from

cracking. For that purpose, one prepared a mixture of wet clay,

mud and a lot of straw as well as other organic material from

plants, traces of which were found on coffins at Deir el-Balah

(Dothan 1979, 99). One would bring this wet mixture in layers

onto the outside of the dry coffin which would have immediately

made a good bond. Meanwhile, a small fire was kindled in the fire

channel the entrance to which was constructed so that it could be

covered by a vessel or a large shard at the entrance, to muffle

the fire, in order to prevent certain cracking by increasing the

temperature too rapidly (see Fig. 1b). Instead, throughout the

initial three hours, the heat would have to be kept relatively

low, between 2-300 degrees Celsius, and this would be made

possible by repeatedly placing the vessel or a large shard into

the stoking opening.

Whereas in modern kilns, pyrometric pyramids (wrongly called

"cones") are inserted to check the heat of the kiln, in ancient

times the potter would do it by eye, using small pierced holes,

observing the change in colour at the inside of the kiln. In the

coffins, however, these holes were placed at certain intervals in

the back of the coffin itself and, all facing upward, since the

coffin was laid on its belly over the V-shaped ditch.

At the same time, the small pierced holes served the purpose of

having an extra outlet for the smoke, so that the holes would

have also been visible through the mud-mantle. This also explains

why the coffin did not have holes in front; they were not

required for the firing. Ornan states that the "holes in the

backs of some coffins were probably intended for drainage" (Ornan

1986, 121). However, she does not explain the cut hole at the

foot-end of the coffin which would have been at 20 cms above the

ground, and thus useless for "drainage". At Beth Shean, for

example, a neatly cut out hole of about 15 cms diameter was found

in the bottom of a coffin (Rowe 1930).

According to the present scenario, the hole at the foot served

to let the hot gases from the inside of the coffin/kiln, escape

into the chimney, with which it was connected (see Fig. 3).

It is suggested here, that these holes were for the firing of

the coffin and not for "airing" the corpse. The openings in the

back were spy holes for the potter who, peeping through them at

regular intervals, would be able to see whether the fire had

reached the entirety of the coffin from within. This would have

been shown by the glowing from within which starts at 700-750øC.

He then closed the holes with wooden pegs and eventually with

mud, whereas the fire would have been maintained at the same

temperature for the duration of approximately 1-2 hours. At that

stage, no fuel was added and the stoking hole was closed, as was

the outlet of the chimney.

During the entire firing process, the ancient potter kept an

eye on the fuel supply, but above all, on the outer surface of

the covering mud layer which tends to dry and break. In order to

prevent the breaking of the outer mud mantle, he would repeatedly

add fresh mud and smooth it all over. Then the entire body of the

coffin was covered with a 5-6 cms. thick wet mud layer, as shown

in the drawing of Fig. 3.

In sum, the firing of the coffin would haven taken eight hours,

the first three at low temperature during which time the covering

of the coffin with mud and straw took place, then 2-3 hours in

order to bring the temperature up to 700-750ø C. and finally

maintaining this temperature for an additional two hours.

After a slow cooling period of 12-16 hours, the mantle of dried

mud was removed and the coffin would be ready to be taken away.

No traces of the mantle have been found, for the simple reason

that the "mud-mantle" was not fired into a ceramic. The dried mud

would disintegrate when in contact with rain or ground water.

Traces of straw, however, were found on some of the coffins as

mentioned above.

On the other hand, a thick black layer appears in a photograph

(Dothan, 1979, Fig. 69) of the hole dug to place the coffins in

the cemetery. Although the excavator did not describe the layer,

it seemed to be of ashes. If this is the case, the coffins were

fired near the future grave and the ashes were mixed with the

sand which covered the graves. Another problem is the human

content of the coffins (footnote 2.)

If this unique way of firing the coffins is the right one, it

would corroborate another Deir el-Balah--Egypt connection,

because the majority of similar coffins was first made in Egypt,

but perfectionated in Deir el-Balah.

Conclusion

The anthropoid coffin depicted in Fig. 2 was fired in a way

similar to the statues depicted in Fig. 1. There is sufficient

archaeological evidence that in the Late Bronze and Iron Age I,

coffins at Deir el-Balah were made in this fashion. The novelty

of the firing in this manner described in the present study,

today, as well as in antiquity, consists of the fact that wet mud

was used to cover a clay object while the firing was taking

place,-- a procedure which has often been considered a "taboo" in

the pottery manufacture trade.

Footnotes

Footnote 1. The excavation report of the cemetery at Deir el-

Balah (B. Arensberg and P.Smith at Dothan 1979, 92) only mentions

that sometimes in each coffin more than one or even two and three

corpses have been found. No scholar has given a satisfactory

explanation of this phenomenon. Were people buried together

because they died at the same time? If not, the coffin would have

been dug up and after so many years this would have been a major

undertaking because the burial itself makes the coffin to

disintegrate.

Footnote 2. For an exhaustive over-view of the different styles

and controversies concerning the anthropoid coffins, see Tr.

Dothan 1982 and Tr. and M. Dothan 1992.

�REFERENCES

- ALBRIGHT, WILLIAM F. 1932: An anthropoid clay coffin from

Sahab in Trans-Jordan, in American Journal of Archaeology 36, 295

ff.

- DOTHAN, TRUDE 1973: Anthropoid Clay Coffins from a Late

Bronze

Age Cemetery near Deir el-Balah, in Israel Exploration Journal

23, 129-148.

- DOTHAN, TRUDE 1979: Excavations at the cemetery of Deir el-

Balah, Qedem 10, Monograph of the Institute of Archaeology of the

Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- DOTHAN, TRUDE 1982: The Philistines and their material

Culture, Jerusalem, Israel Exploration Society Chapter V,

252-288.

- DOTHAN, TRUDE AND MOSHE 1992: People of the sea, New York,

57-75.

- ENGELBACH, R. 1915: Riqqeh and Memphis VI, London, 18 and 21;

Pls.IX:18, XIX:1; XXXIV-XXXVIII.

- HENNEQUIN, L. 1939:

Trois sarcophages anthropoides en poterie trouves a Tell Duweir,

in Melanges Syriens offerts a R. Dussaud II, Paris, 965-974.

- MACDONALD, E. STARKEY, J.L. AND HARDING, L. 1932: Beth Pelet

II, London, 25; Pl. LIII.

- NEVILLE, A. AND GRIFFITH, F. 1890: The mound of the Jew and

the city of Onias,: The Antiquities of Tell Yehudiyeh, London,

15-17; 42-48 and Pls. 12 and 13.

- ORNAN, TALLAY 1986: A man and his land, Highlights from the

Moshe Dayan Collection, Catalogue 270 of the Israel Museum of

Jerusalem, Chapter IV, 57.

- PERLMAN, ISADORE, ASARO, FRANK AND DOTHAN, TRUDE 1973:

Provenance of the Deir el-Balah coffins, in Israel Exploration

Journal 23, 147-151.

- PETRIE, WILLIAM M. F.1888: Tanis II, 17; Pls. I and

III.

- PETRIE, WILLIAM M. F. and Olga Tufnell 1930: Beth Pelet I,

London, 6-9; Pls. XIX and XXIV.

- REISNER, G.A. 1910: The archaeological survey of Nubia,

Report for 1907-8, Vol. I, Cairo, Fig. 46, Pl. 36.

- ROWE, A. 1930: Beit Shean Cemetery, 139 ff; Figs. 12,53:4 and

80;9,52:1-4.

- ROWE, A. 1930: The history and topography of Beth Shan I,

Philadelphia, 37, Pl. 17.

Fig. 1b. The Art-ceramic belly of an animal with mud mantle and

muffling slab at the opening of the stoking hole.

Fig. 2.a-d. Pen drawings of the front, the lid, the back and the

section of a ceramic anthropoid burial coffin similar to the ones

found at Deir el-Balah.

Fig. 3. The probable way of the firing of anthropoid coffins

during Late Bronze II and Early Iron Age I. The coffin itself is

the kiln, covered within a mantle of mud and straw.

Please, send comments and/or questions regarding

the manufacture of Anthropoid Coffins to:

Jan

Gunneweg

Copyright of all which has been reported here:

Jan Gunneweg, The Hebrew University February 1997

Since February, 1, 1997,  people have leafed through this

Coffins Paper

people have leafed through this

Coffins Paper

Click here for returning to

Gunneweg's Homepage